|

In Search of Your Ancestors?

A column on genealogy by George Farris October 23, 2015

© Copyright 2015, Inside Anderson County, All rights reserved.

|

In Search of Your Ancestors?

A column on genealogy by George FarrisOctober 23, 2015

29. Tracking Ancestors in Old Tax Lists In these periodic columns I have illustrated some of the sources and methods that I've found useful in conducting my own family history research. These have included some problems and issues and the methods for attacking them that are common to just about everyone involved with genealogy and some that may be more location specific and not as generally applicable. Some of us find that we have ancestors who were among the colonial settlers in the southern American colonies before and shortly after the American Revolutionary War and find that many of the common records no longer exist or weren't even kept in the first place. So it is a challenge locating and tracking these ancestors - and some are just lost to history and can't be identified. In this column I'll address one kind of record source that I've found to be quite useful - local tax records for the late 1700s and early 1800s. As usual, I'll illustrate with examples from my own research.

Local Tax Records

While Federal census records are an essential tool in tracking the location, movement, and makeup of families that you are trying to research, they only provide a data point every 10 years, and didn't exist for most places before 1800. Throughout the 1700s and 1800s there was a rapid migration of the U.S. population westward and some families moved numerous times over a period of 10 years. A potential data source for tracking families within these 10 year windows are tax lists where they exist. They do not contain as much information as census records but can be very useful for tracking a specific family's location - especially during the years before there was a census. In Virginia, researchers have used a collection of individual tax records from most counties to compile something akin to a census for the years around 1790 and 1800. I've found tax lists to be very useful in tracking ancestors in Virginia and Kentucky for periods when other records are very sparse or nonexistent for them.

As is also the case with census records, when searching for an individual in tax records you are likely to encounter several common issues. First, realize that the enumerations were done by many different individuals. Some were very careful - but many weren't. There are the usual issues of legibility of handwriting and deterioration of paper records over many decades before they were microfilmed. But, beyond that, the people doing the enumerations just wrote down what they thought they heard from the head of the household at the time they made their visit. In addition to spelling the names in their own way, they often misunderstood the names. The result is that when you look at the records for the same family over a period of years in tax lists there will almost always be variations in names for what is obviously the same person.

In a previous column I mentioned that the first records that I've found for one of my gr.gr.gr.grandfathers, Moses Estes, are the tax records for 1788 and 1789 in the Cumberland River settlement in Tennessee. His parents and siblings had joined James Robertson's group in traveling overland through Kentucky from the Holston River area to Fort Nashboro in 1779. Also, tax lists have been the primary source of records for my Farris ancestors in KY in the late 1700s and early 1800s. But tracking them in Virginia in the 1700s has been even more challenging because there are fewer records and several other unrelated Farris families existed in Virginia as well as in Kentucky during the 1700s.

Under Virginia law the individual counties compiled lists of "tithables" that listed the heads of families and taxable items. Except for widows who were living on their own as the head of household with no sons over 21 these lists do not include any names of women. There are relatively few of these tithable lists that exist before 1780, but beginning in 1782 they are fairly complete except for several "burned" counties for which few records exist at all. Since many Virginia records were lost during the Revolutionary War and the Civil War, the lists of tithables or heads of families are important record sources where they exist.

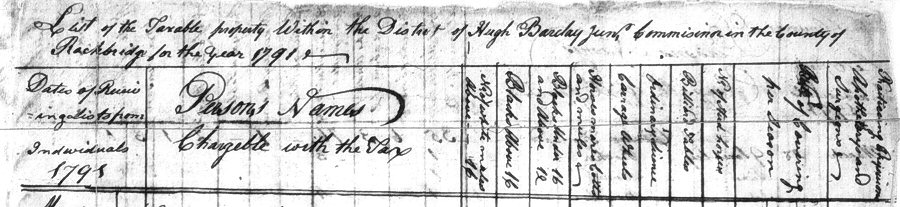

After 1779, according to Virginia law, each commissioner in each county beginning on March 10 was to visit every head of household subject to taxation within his district to receive an affidavit on his taxable persons and property. Usually these were obtained orally, but they could also be provided in writing. The commissioner was to turn in to the clerk of courts by May 31 a list showing the date each statement had been received, the person chargeable, the names of all free males subject to tax, the number or quantity of every "species" of taxable property. The law specified a form that showed the names of all free male tithes, the number of white males above 15 and under 21, the number of blacks above 16, and the number below 16 in each household. Only the 1787 return showed which white tithables were under 21. It was also the first year that some personal property other than slaves was taxed. These new "species " were horses, cattle, carriage wheels, ordinary licenses, billiard tables, number of stud horses and the rate of covering per season, and finally practicing physicians, apothecaries, and surgeons.

Below is an example of the headings of forms illustrating the variety of information collected. Note that there were separate columns such as those for Billiard Tables and Ordinary Licenses which didn't apply to most of the people in. (An Ordinary was any establishment that provided food, drinks, boarding, and stable facilities for travelers or longer-term boarders - generally simply called Taverns.)

1791 Rockbridge County, VA property tax list headings

1791 Rockbridge County, VA property tax list headingsI've previously written about the importance of researching associated families when tracking a migration of a particular family because interrelated families often migrated together. The example used in this column will focus on tracking the family of William Bonnell/Bunnell through Virginia and on to Kentucky since he was probably also an ancestor of mine and his migration was important for tracking the migration of William Farris (my gr.gr.gr.grandfather) and his brother John Farris.

William Bunnell

From DNA analysis of known direct male line descendants, it is known that the subject William Bunnell was a direct descendant of the original William Bunnell of America who first arrived in the New Haven settlement in 1637. While numerous descendant lines from this original Bunnell have been documented, some have not. The exact ancestral connection of the subject William to the original William has not been proven. There are a lot of variations in the spelling of the name but Bonnell and Bunnell are the most common, sometimes with one "l" or one "n." While the VA/KY William signed his name William Bonnel, most records list him as Bunnell or Bunnel. The first record that can reasonably be ascribed to him is his name along with a Samuel Bunnell in the 1768 list of tithables in Loudoun County, VA. After that, there are records for both a William and Samuel Bonnell in Loudon County through 1771, and in Spotsylvania County in 1772 and 1777. The 1777 record is the last one for this Samuel Bonnell who was listed to be "of great age" in a statement in Loudoun County in 1771. He is believed to have been the father of the subject William Bunnell. Except for one record in Loudoun County in 1771, one in Albemarle County in 1785, one in Rockbridge County in 1792 and three in Botetourt County in 1795, 1796 and 1797 we have to rely on tax/tithables lists to track William Bunnell's migration through Virginia and on to Kentucky.

He is listed in the 1782 Spotsylvania County tax list as William Bunnell and in 1783 as William Bonnell. The 1783 list is the last record for him in Spotsylvania County. After that the Bunnell family began their migration from their location on Plentiful Creek in Spotsylvania County, probably through Louisa County to Albemarle County. At about the same time William and John Farris left from their location about 30 miles south of the Bunnells on the South Anna River in Hanover County and began their migration - also through Louisa County to Albemarle. There are no Bunnells on the tax lists in Albemarle. However, William Farris is listed there in 1785 and 1787 and in July, 1785, John Farris married Anne Bunnell, one of the daughters of William Bunnell, in Albemarle. After this marriage, the John Farris family always lived near the Bunnells for about the next 30 years.

The Virginia tax lists are compilations of individual lists prepared by the various precinct commissioners. These individual lists were then combined at the county level into a nominally alphabetized list in which all names starting with "A" were grouped together followed by all names beginning with "B" etc, Within these groups the names were not alphabetized but instead were generally listed according to a date - the date when the individual's affidavit was provided to the commissioner. This makes it possible to identify neighborhoods where individuals were listed on the same date. Since in essentially all of the tax lists that include both John Farris and William Bunnell they are listed on the same date it's clear that they always lived near each other.

It appears that Rockbridge County VA was the intended initial destination for the Bunnells, since the tax lists show that they and John Farris remained in Rockbridge County for nearly eight years. Both first appear in the 1787 list and the Bunnells remained there through 1794. John Farris was listed for the same period and remained there through the 1795 list. The one Bunnell record other than tax lists is a marriage of Rebecca Bunnell in 1792 for which William Bonnel signed the marriage bond.

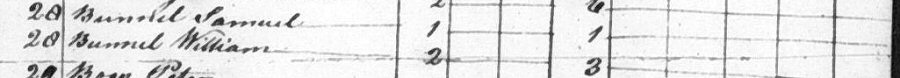

In 1795 William Bunnell was listed in adjacent Botetourt County and one of his older sons, Samuel Bunnell, was listed separately. In the 1796 list they had been rejoined by John Farris, who was then listed in Botetourt through April 3, 1798. William Bunnell was named in suits regarding debts in 1795 and 1796. The Bunnells - William, Samuel, and "the wife of William Bunnell" were named as witnesses in a case in the Botetourt County Court Order Book in November, 1797. It appears probable that both the John Farris family and the Bunnells then made the long journey to Mercer County, KY during 1798. In 1799 records for both families began appearing in Mercer County.

While these records document the migration of those families, the absence of William Farris from any of these tax lists after 1787 is also significant. He does not show up in Rockbridge tax lists with his brother and the Bunnells and it appears likely that he went on to Kentucky at the time the others settled in Rockbridge County, VA. Since there were other people of the same name in VA and KY it is not possible to be certain which records pertain to him. The William Farris listed in tax lists in Woodford and Franklin County, KY during much of the 1790s was probably him. After the Bunnells and John Farris arrived in Mercer County, a few miles to the south, he rejoined them there and shows up in a few records there through 1809. Apparently William Bunnell died shortly after 1805 (although no will or other death record has been found) and, over the next few years, his 12 children and their families moved in several directions from there. Some of them, including the John and William Farris families, went to Green, Hart, and Barren Counties, KY. From Green County William Farris went on to the Illinois Territory in 1814 and was followed by John Farris in 1817. Tax lists for Green County document both families from 1810 through 1813 and Hardin County tax lists show that John moved there for a few years to join two other Bunnell families before joining his brother In Illinois.

Where to find Tax Lists

While you may occasionally find a tax list for a specific year for a specific county that has been transcribed by someone and is searchable, most tax lists are simply unindexed images of the original documents. Searching them on microfilm can be quite tedious, especially if you are not sure where your ancestor might have been living during a specific year. The microfilms of tax lists for specific counties can often be found in a local library in that county. But, if you don't know what county to look in and need to access films for numerous counties then you will need to search at a state library or archive that includes a complete collection of films such as the Kentucky State Library and Archives in Frankfort or the Library of Virginia in Richmond. If you can narrow down your search to one or two specific counties you can order the microfilms through a local LDS Family History Center and do your searching there.

For Virginia tax lists there is another good resource called Binns Genealogy which was developed and is maintained by Steve and Yvonne Binns at www.binnsgenealogy.com. You can purchase CDs of individual county tax lists from them. But they have also endeavored to make many Virginia tax lists easily accessible by converting the microfilm images to pdf format and putting them on-line, accessible for a nominal annual subscription fee. I used that resource to obtain much of the tax list information involving the Virginia part of the Bunnell/Farris migration described above. The information for the Kentucky part of this migration resulted from research in several local libraries and court houses as well as the Kentucky State Library and Archives.

Some Examples

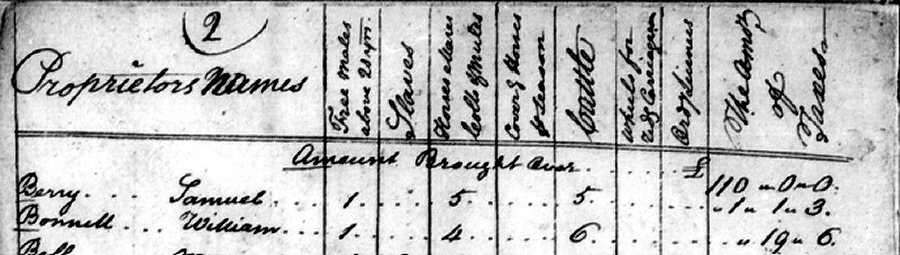

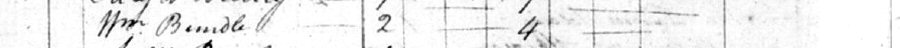

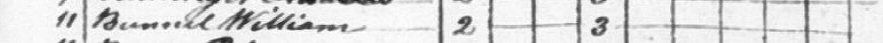

The following images illustrate the variation in names listed for the same individual over a period of years. Our subject was listed as William or Wm. Bonnell, Bunnell, Bunnel, Bundle, etc. in the tax lists. In marriage bonds he was referenced as Bunnell in the text but signed as Wm. Bonnel.

1783 - Spotsylvania County, VA

1783 - Spotsylvania County, VA

Note that the earlier lists did not include as much information as those after 1787

1791 - Rockbridge County, VA

1791 - Rockbridge County, VA

1794 - Rockbridge County, VA

1794 - Rockbridge County, VA

1795 - Botetourt County, VA

1795 - Botetourt County, VA

1796 - Botetourt County, VA

1796 - Botetourt County, VAAcknowledgement: John G. Bunnell, another researcher of the William Bunnell family, recently visited the courthouses in Loudoun, Spotsylvania, Albemarle, Rockbridge, and Botetourt Counties, VA and reviewed all of the available county records. While there were very few records for the Bunnell family other than the tax lists and the two marriage bonds that had been found previously, he did find several references to William Bunnell in the Botetourt County Court Order Books.

Previous Columns in this series1. Beginning your search

2. "Source Data"

3. More About Data Sources

4. Additional Data Sources

5. LDS and Data From Other Countries

6. Census Records

7. Military Records

8. Land Records

9. More About Land Records

10. Land Records as a Source of Family Information

11. Wills and Probate Records as Sources of Family Information

12. Biographies, Obituaries, Old Newspapers, and Family Lore

13. Sharing Family History Research

14. Some Genealogy Web Sites to Use With Caution

15. Genealogy & Local History

16. Tracking One Specific Ancestor

17. What Next?

18. Tracking One Specific Ancestor - 2

19. Importance of Family Groups in Tracking Ancestors

20. Two new on-line genealogy research tools

21. Some books for family history researchers

22. Census time again

23. A tale of the professor and the horse thief

24. Family artifacts, mementos, letters, etc. as a source of genealogy information

25. "Find A Grave" - Another potentially useful genealogy research tool

26. The 1940 U.S. Census

27. A "Dead End"

28. DNA and Genealogy

© Copyright 2015, Inside Anderson County, All rights reserved.