|

In Search of Your Ancestors?

A column on genealogy by George Farris January 4, 2010

© Copyright 2008, Inside Anderson County, All rights reserved.

|

In Search of Your Ancestors?

A column on genealogy by George FarrisJanuary 4, 2010

22. Census time again

"The actual enumeration shall be made within three years after the first meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent term of 10 years, in such manner as they shall by Law direct."

-- Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution of the United StatesThe first census of the United States was carried out in 1790 - and, since then, a census has been taken every 10 years - in accordance with the Constitutional requirement. In April of 2010 it will be time for the twenty third census of the United States. It will be a relatively simple census this year as compared with some of the past ones - with only 10 questions. The details of this latest census will not be made available to the public for another 72 years. That time period was set many years ago when life expectancy was such that there was not a high probability of finding information about living people at the time of the release of the data. However, with people living considerably longer than used to be the case many living people could find data listed about themselves in the fifteenth census (1930) which was released eight years ago. And in two years, on April 1, 2012, many more of us will see early records including us in publicly available census data for the sixteenth census taken in 1940.

People doing family history research always look forward to the release of the next census in the series in order to help fill in details about their own family lines. So it's a good time to think again about census data and its use in your own genealogy research. In a previous column (number 6 in this series) I addressed some of the issues involved with the use of census data. The bottom line is that a series of census records about a family can be very valuable in your research - but that any one individual record, and any published extraction or transcription of it, is very likely to contain errors in details. And in the 10 year time span between the federal census records many people moved numerous times - so it's necessary to look for other records to find out where people were living and what they were doing in between those once-a-decade records. As mentioned in that previous column, several states routinely took their own census half way between the federal census years for some periods. I've found the Illinois, Iowa, and Kansas state census records to be very useful in filling in some of the gaps - but these records are subject to the same problems as the federal census records, so they also need to be used with caution.

To quote from the earlier column:

"In searching for an individual or a specific family in census records you are likely to encounter several common problems. First, realize that the census enumerations were done by many different individuals. Some were very careful - but many weren't. There are the usual issues of legibility of handwriting and deterioration of paper records over many decades before they were microfilmed. But, beyond that, the people doing the enumerations just wrote down what they thought they heard from whomever was available at the household at the time they made their visit. In addition to spelling the names in their own way, they often misunderstood the names. Given names were often recorded by whatever the individuals were called within their family - by initials or nicknames in many cases. Ages were recorded as best the person providing the information could remember - and, if they were working in the fields or elsewhere they were not about to go look up the exact information from a family bible or other source. The result is that when you look at the records for the same family over a period of 3 or 4 or 5 different census records there will almost always be discrepancies - most commonly in ages - but also in names. So, especially for ages, census records are just a starting point - and an individual record should not normally be used as a definitive source record for age of the person."The ease of availability of a lot of census data on-line, including in many cases digitized images of the original records, continues to lead some researchers to assume more from the data than the accuracy of the data may warrant. Census records are relatively easy to access while other more localized records can be very difficult and time-consuming to locate. So people tend to rely too much on individual census records as being definitive. While a series of three or four censuses for the same family tends to illuminate the discrepancies and uncertainties, one individual record used with no other supporting documentation can lead to erroneous conclusions.The example below of three census records for the same family for 1850, 1860, and 1870 may help illustrate some of the above points. In this case, descendants researching this family have done the necessary research of other local records to expand on their understanding of the family and to uncover most of the errors and discrepancies found in the census records.

Example: The family headed by Mary Ann Rebecca Downey Whipp Jones Judd

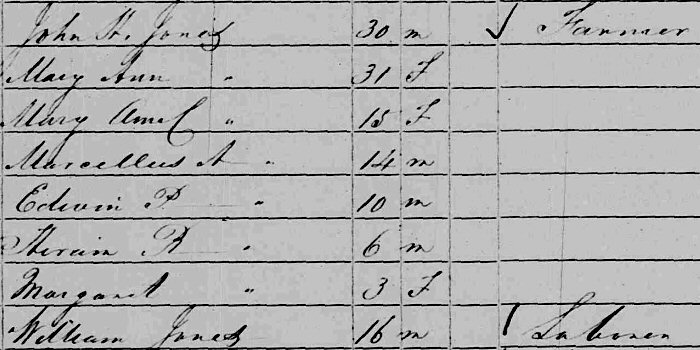

1850 Census - Tazewell County, Illinois:

In this census, Mary Ann's second husband, John H. Jones is shown as the head of the family.

This record illustrates several of the problems mentioned above. While this record is somewhat faded, the handwriting is better than in many census records. But it is still easy to misinterpret some of the names- and the census enumerator apparently wasn't given a key piece of information - that being that three of the children were from Mary Ann's previous marriage and their surnames were Whipp rather than Jones. In the transcription of the record for indexing, the name of one of the children was shown as Mary Amel but her name was actually Mary Ann C. Whipp - a point that is clarified by the 1860 census for this family in Mason County, Illinois. Marcelles A. Whipp shows up with the proper name in later census records in Illinois, Nebraska, Kansas, and Colorado.. But some of those researching this family never did find the person listed as Edwin P. Jones - even when they realized that his surname was also Whipp. This was a case of the enumerator recording what he thought he heard - but the first name was actually Adrian rather than Edwin. This was clarified by a marriage record in 1860 and by his Civil War service record - which was short ... He enlisted in September, 1861, but died of jaundice in February 1862. The 3 year old girl shown as Margaret in the 1850 census was known throughout the rest of her life (and in subsequent census records) as Amanda - Margaret being her middle name.

By the time of the 1860 census Mary Ann Jones was listed as a widow, age 45, living in Mason County, Illinois - with the children listed as Hiram R - 16, Amanda M. - 14, William D. - 9, "Marah" - 6, Emily E. - 4, Louisa A. - 1, and Mary C. Whipp -25. So Mary Ann had given birth to 4 more children during the 1850s and her 2nd husband had died after 1858.

By 1870 Mary Ann was in Blair, Washington County, Nebraska with some of the children - Hiram - 25, "Downey" (William D.) - 19, and Emily - 14. But, between 1860 and 1870 she had been remarried - with her name listed as Mary A. Judd - age 52. Her oldest son, Marcelles Whipp, was married and living nearby with his family. Amanda M. Jones and Mary C. Whipp had both married in Omaha, Nebraska in 1868. And the Marcelles Whipp family shows up in the 1865 Kansas state census - in Douglas County. So it is obvious that this family had moved several times during the 1860s.

While I've used this series of records here to illustrate some of the problems inherent in using census records for family history research, they were actually just an interesting sidelight in attempting to resolve a deeper census mystery that I have been pursuing with my 4th cousin Jack E. Stockman. Jack is a great grandson of the above Amanda Margaret Jones who married Edward D. Stockman in Omaha, Nebraska in August, 1868. We have researched Amanda's family as well as the families of apparent siblings of Edward in an attempt to better document Edward's background. There has been only one census record found listing Edward - in 1880 in Denver, Colorado (he died there in 1889). Although it is evident that he was the son of Jane and Charles W. Stockman (a brother of my gr.gr.grandmother Amelia H. Stockman), no definitive proof has been found. Some of the census records for Jane and Charles and their family were not easy to find - since they were listed as "Stockholm" in 1850 in Michigan and as "Stocton" in St. Joseph, Missouri in 1860. In between, they were found in Iowa in a state census taken in 1856. In 1870 they were in Illinois - and in 1880 in Denver, Colorado near Edward and Amanda. The problem is that none of the census records for 1850, 1856, and 1860 lists Edward with this family. Nor can he be found anywhere else - nor anywhere in the 1870 census with Amanda.

This is an ongoing mystery that hasn't yet been resolved - that also illustrates the inadequacy of census records alone as a source of family information. The 1850 census for his parents' family doesn't list Edward - but does list a son named Sidney of the same age - born in 1846. In the 1860 census, the family was on the edge of the frontier and, like many youth of that age, Edward was very probably away on his own off looking for adventure. He showed up in Omaha, not far from St. Joseph, by 1868 when he and Amanda were married. But, in the meantime, according to family oral history, he had spent some time hunting buffalo with William F. Cody ("Buffalo Bill"). That would put him in far western Kansas and the eastern part of the Colorado territory around 1867 when Cody was supplying buffalo meat for the track-layers on the Kansas Pacific Railroad.

We will continue to work on that particular research problem. I use it to illustrate that, while federal census records can be a useful (and essential) starting point for family research, they can also be a major source of frustrations - and can lead you astray if they are not augmented with other research.

Previous Columns in this series1. Beginning your search

2. "Source Data"

3. More About Data Sources

4. Additional Data Sources

5. LDS and Data From Other Countries

6. Census Records

7. Military Records

8. Land Records

9. More About Land Records

10. Land Records as a Source of Family Information

11. Wills and Probate Records as Sources of Family Information

12. Biographies, Obituaries, Old Newspapers, and Family Lore

13. Sharing Family History Research

14. Some Genealogy Web Sites to Use With Caution

15. Genealogy & Local History

16. Tracking One Specific Ancestor

17. What Next?

18. Tracking One Specific Ancestor - 2

19. Importance of Family Groups in Tracking Ancestors

20. Two new on-line genealogy research tools

21. Some books for family history researchers

© Copyright 2008, Inside Anderson County, All rights reserved.